If I'd Known You Were Gonna Die, I Wouldn't Have Baked You That Cake

It's been 41 years since my dad died. When do I finally get to let go of this grief and anger?

April 11, 1984, was my father’s 46th birthday.

My sister Christy* and I were home with our dad, as our mother had just started working a new job, the first she’d had outside the house since she’d married and had the two of us.

I was fourteen. Christy was eleven. We adored our father and wanted to do something special for his birthday. I don’t remember what we got him for presents, but I do remember—o, lord, how do I remember—I decided I would bake him a cake.

While Christy and I banged around in the kitchen, he read in our parent’s bedroom, listening to whatever the South Florida classical music public radio station was playing.

As someone who loves to bake, and considers himself pretty damn good at it now, it’s hard to re-embody a time when I didn’t know what the hell I was doing in the kitchen. On this night, however, I didn’t. I’d had a previous baking disaster, which was the moment I learned that baking “from scratch” didn’t mean you just dumped things into a bowl and expected it to transform into a gorgeous frosted cake.

On this night I was using a recipe. I don’t remember which recipe, or what kind of cake, or what flavor frosting for that matter. There’s so much I don’t remember.

I do remember the moment my sister and I called our father into the kitchen once the cake was finished. Our giddiness, thinking we were surprising him as if he hadn’t been listening to us for the last hour. The “4” and “6” numeral candles on the cake glowing brightly.

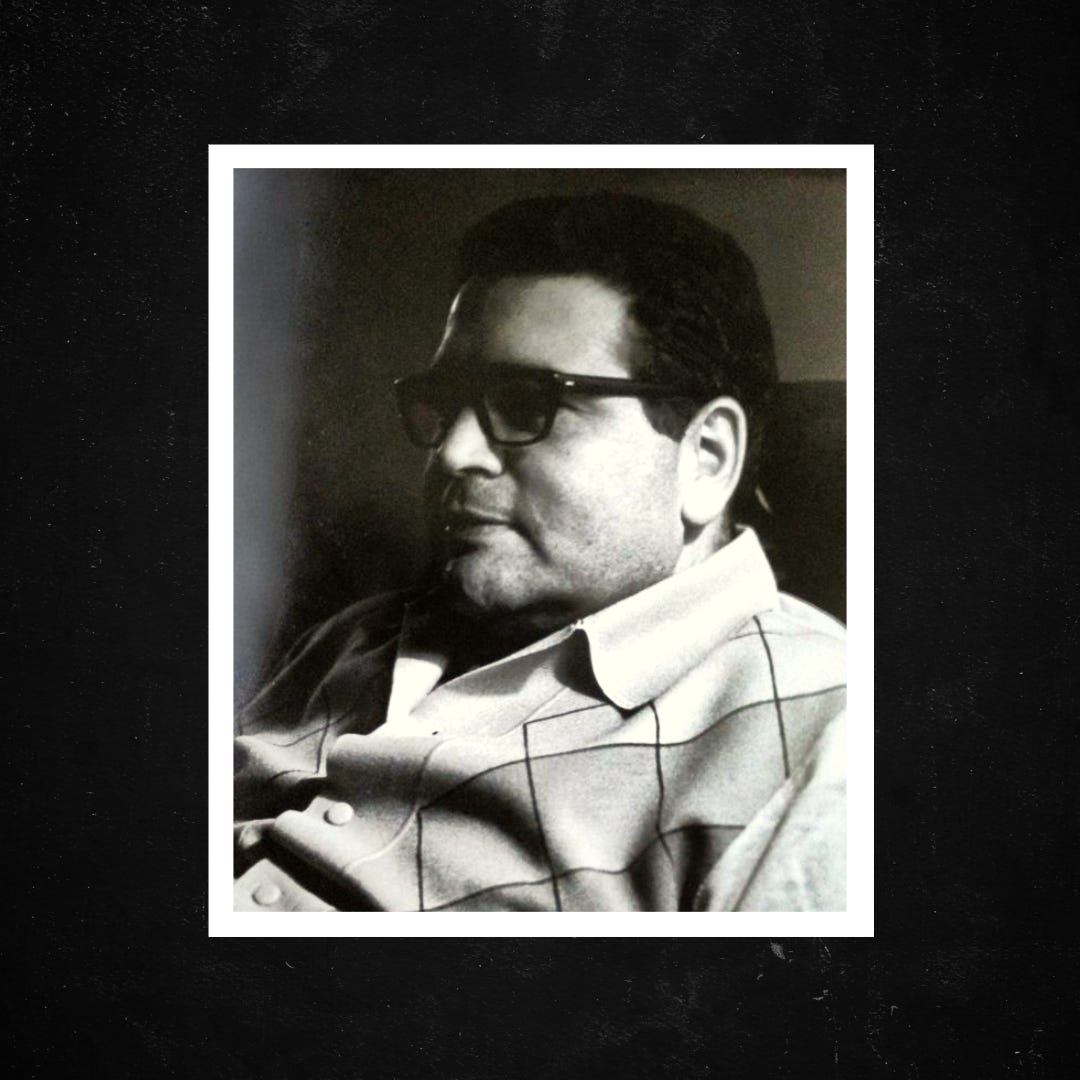

And the image I will never forget: my father approaching the table, his eyes shining, and a big grin on his swarthy face—burned into my memory, flashbulb bright and clear—with a smile that radiated the love and joy and humor that embodied his spirit.

It’s so clear in my mind, I’d swear there was a photo of it. I’ve searched for that picture for years, and I can’t find it (if it ever even existed).

But I wish I had it. I wish I could see that moment again, even if just in a photograph—because it was the last time I ever saw my dad smile like that.

The next morning at about 8 am, he died in the shower while we were at school, and I never saw him again.

Much of the next day—hell, the next months, and truthfully the entirety of 1984—remains a blur to me.

But that indelible moment, and that cake, have stuck with me for more than forty years.

The cake stopped being a cake. It became a symbol. Of love, yes—but also of failure. Of all the things I couldn’t possibly have known and all the ways I somehow felt I should have. That’s what grief does, especially to us as children. It teaches you to find fault in your most innocent moments.

It wasn’t a perfect cake, so did he detect an imperfect kind of love from me? Or worse—I fed him cake the night before he died. Could it somehow be my fault?

Looking back, I know that’s a ridiculous conclusion. I was fourteen. I wanted to make something nice for my dad’s birthday. But over the years, that cake became fused with his death in a way I couldn’t untangle. It became the last act before the unthinkable. A celebration immediately followed by absence. The candles burned, and then—nothing.

In the lifetime I’ve spent processing his death, I’ve gone through almost all 973 stages of grief. I’ve found and excavated so many more than Elisabeth Kubler-Ross ever identified. She missed all of the ones associated with cake.

But the anger is real. Anger is an entire category of stages of grief, with at least hundreds of forms: sharp anger; dark, smoldering anger; deep titanic anger, welling up from the depths. Anger for every shade and season.

It didn’t come right away. It built slowly, over time, collecting in small pockets. I didn’t have the words for it at first, but it was there.

Anger at how sudden it all was, at how completely the world could change in one morning.

Anger that I never got to say goodbye.

Anger that no-one prepared me for how long grief can last, or for how it mutates, and how it resurfaces at unexpected moments.

Anger at how people eventually stop asking, assuming you’ve moved on, when really the shape of your life has been permanently altered.

Anger at a discontinuity so deep I literally wasn’t the same person from before to after.

For much longer than I care to admit, when that fury burned brightest within me, I’d mutter angrily to the shade of my father—always with me, in all things—how I never would have baked him that damn cake if I’d known what was coming next.

It was a cruelty to a ghost, born of that desperate, hot anger, as if the cake itself was the pivot point upon which all of history hinged.

But here is an unavoidable truth—there’s a version of me that only exists because of that loss, someone forged in the absence. I can track the ripple effects across decades. It’s in the way I approach love, fear, and celebration, as well as the things I still don’t trust to last. I’ve built a life—carefully, thoughtfully—and there’s joy in it, accomplishment, even peace.

But I also carry a small, hard kernel of fury tucked inside, a reaction to something that never should have happened the way it did.

And with the grief, and the anger, and the long passing of time—then there’s everything he missed. Everything I wish I could’ve shared with him. He never saw the adult version of me. He never knew I was gay—at least, he never heard me say it, and god knows I have no idea if he ever suspected or wondered. Would it have changed the nature of his love? I’d like to think not, but I have no way of knowing for sure.

He never tasted anything I’ve baked since, like his own mother’s snowball cookies, a recipe I inherited from my grandmother. He never met the people I loved and never saw the full arc of who I became. He didn’t get to know what I care about, how I’ve changed, how I’ve stayed the same. I love classical music and opera because of him. I love astronomy and science. I love traveling and exploring new cultures. All of these are gifts from him that I never got to share, or experience with him—or thank him for.

Every beach I see reminds me of him, not just because he loved beaches, but because we sprinkled his remains into the Gulf Stream off the Florida coast. He’s everywhere now, at every beach I’ll ever go to for the rest of my life.

And here’s a ridiculous thing I just realized, all these years later: I don’t have any idea what kind of cake he actually liked.

I’ve outlived him by nearly a decade now. And still, I think about that cake. About how it held so much love. And how it became the last gesture I made before everything fell apart.

So when people talk about “letting go,” I never quite know what they mean. The grief has softened, yes. The anger isn’t as sharp. But letting go? I don’t think that’s the goal. It’s more about learning how to hold it differently. Not like a wound, but like a scar—something that doesn’t hurt the same way anymore, but still tells the truth about what happened.

That cake was the last gift I gave my father. It wasn’t perfect. But it was real.

And for better or worse, it’s what I had to give.

Forty-one years later, I still hold that moment with me. Not because I’m stuck. But because some things are meant to be carried. Maybe forever.

I just didn’t know it would be cake.

* names changed for privacy.

Thank you for opening up your soul and telling this story. I’m so sorry for what you carried through the years. My Dad died Thanksgiving Day 1971 and I so resonated with your grief 🙏🙏

My mom died of cancer the day after her birthday, she was 51, I was 26. We knew she was leaving us and yet I had to do something for her on her birthday. I bought her a stuffed animal, something soft and tactile she could pet and cuddle for what would be her last 24 hours. She only knew 1 of her 4 grandchildren, my oldest son, and then only briefly. The fury was nearly a living thing. It was directed everywhere, especially at myself. Because, I'd made it my job to be her cheerleader, to transfer as much of my positivity to her as I could. It wasn't enough. She fell into depression and despair despite my efforts, and because of that I'd failed her. I had one job you see. 22 years, and a lot of life later, the wounds have scarred, some days though, the grief taps me on the shoulder, reminding me it's never very far away. The days I think of all she's missed, all I was robbed of, like you, the kernel is still there. Peace to you.