I Lost a Daughter. She Lost Her Third Mom.

On Mother’s Day, I think of Katy, who I loved as my own. I lost her when I lost him.

(Watch me read this story here.)

It’s nearly midnight, it’s 2014, and I’m in bed with the man I left my marriage for over two years ago. We’ve just split for the second and final time a few weeks before, and yet here I am.

He strokes my shoulder and kisses my head while his daughter Katy* sleeps in the room next door, unaware of my presence.

It’s probably for the best.

She’s only five, and for half her young life, I’ve been her acting mother. I’m the only one she can remember, and now I’m the third one she’s lost.

But it wasn’t an act. She felt like mine.

A lost lover leaves a bruise. But losing a child — one so in need of a mom, one who loved me and my daughters — is a singular pain, an ache I rarely acknowledge lest it take me down a mournful path of motherhood not taken.

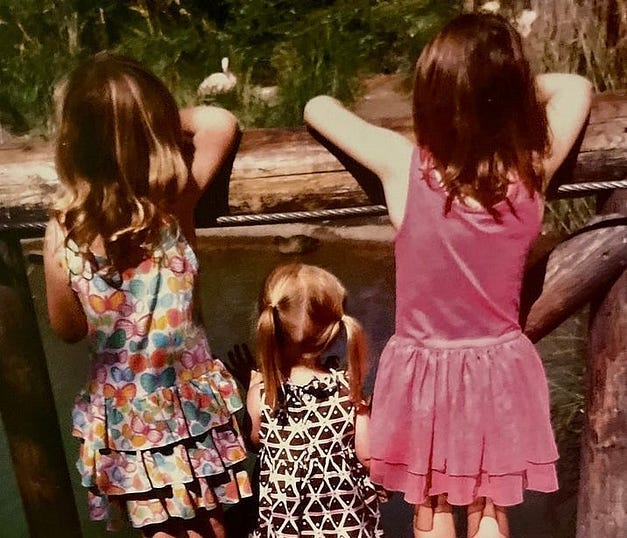

I haven’t revisited this part of my life in years, not even in photographs. I gaze at them now and observe how the images of my three wee girls have faded. As I look at the faces of my two daughters, I can see how they’ve evolved into their teenage selves. I look at Katy and see a question mark, a child frozen in time.

Katy’s story begins as it ends, with loss.

According to her dad, she was born on the kitchen floor; her birth mother, young and drug-addicted, labored alone. He and his wife were 40-somethings who’d nearly given up on parenthood when they got the call — and got their girl. Katy was a beautiful baby, so lovely the adoption service asked to use her photo on the cover of their brochures.

The new parents were thrilled. They couldn’t believe their luck.

Then it ran out.

A year later, Katy’s mom was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Stage four.

By 18 months old, Katy had lost her second mom.

I showed up about a year later. I met Katy and her father because our three girls took gymnastics together. Every Saturday morning I’d sit and talk with this lovely widower and get to know his child, a fierce, bright thing. Katy had such determination, her muscular frame fighting for that next feat — trampolining higher, somersaulting faster, hurling herself into the foam pit with abandon, her grin as wide as the day. I could feel the way her dad glowed as we relished a shared joy in watching our kids bounce about. I was amazed at how radiant they both were, given their catastrophic loss. And what can I say, I’m drawn to the light.

I fell for that man. But the pull to parent this beautiful, motherless child? It was irresistible.

So I took the wildest leap of my life. I left my marriage to be his girlfriend, and to love them both.

Oh, I can still visualize my blue-eyed trio. My two were fairer, dishwater-blonde hair framing their sweet faces. Katy’s hair was darker, fringed around her expressive wide-set eyes and impish grin.

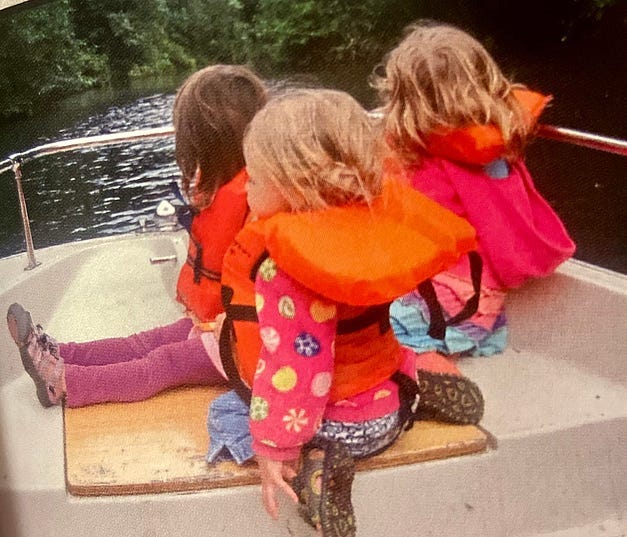

Together we went on countless adventures. At the community pool, Katy’s dad taught my eldest to swim; he’d already shown Katy how and she plunged in with gusto, even taking on the imposing rope swing over the deep end. We beachcombed our Northwest coast, the girls uncovering crabs and seastars and soaking themselves on the shoreline as the frigid tide rolled in. We visited our local candy shop, allowing the kids to fill baggies with rainbow-colored confections till they were giddy on sugar highs. We even took a vacation to a lake house, the kids delighting in boat rides on the placid water, and befriending slimy slugs along the shore. I relished watching their friendships blossom and inwardly beamed even when they’d occasionally spat. It seemed so sisterly.

But my strongest memory of Katy — the time when I felt most like her mom — came when she’d been wearing a Band-Aid on her knee for a week, refusing to let her dad take it off. It was clear the wound was infected but she howled at my suggestion to remove it. Her dad blanched as well; he didn’t want to hurt her. So we made it a team effort.

I held her head in my lap as she wailed. I could feel her fighting me and also leaning in for comfort as her dad yanked off the strip. The wound was angry, a bit fetid. He looked miserable as he cleaned it and applied ointment.

“You’re both going to be okay,” I assured him. He nodded and smiled. And right then, eyes held in support over her little body, it felt like we were her parents, in it together.

I’d worried about whether I could love another child as fully as I loved my own. That day, I knew. A mom’s heart can always expand to love more.

Her knee healed, of course, and we all moved onward, together yet separate.

But I couldn’t connect the dots to see how we could one day fully connect our lives.

Katy’s dad rarely spoke about adoption with her.

For him, it was imperative that Katy recognize his late wife as her mom. She was the one who’d chosen her, even if she hadn’t birthed her.

I understood his reasoning, and felt empathy for his plight. With no bloodline and no memories of her late mom, their connection was tenuous, a wisp of an act of love. I could see little hope that Katy would feel much for her, as gutting as that was, for both of them.

Looking back now, I can see the true sorrow: it was more important to him that Katy remember her late mom than she know her own origin story — or that she learn to love another mom.

He held steadfast to his late wife not only in parenting but also in our relationship. When we first fell in love we spoke about intent. If I left my marriage, I expected to make a life with him and Katy. He promised he wanted that, too.

“Jump, and I will catch you,” he told me.

Two years later, my leap of faith had us stuck on hard, craggy ground.

I can’t blame it all on him. The magnitude of moving from married to single had seismically shifted everything for me: my home, parenting, mental health, finances, all of it. I was overwhelmed by the fallout and underwhelmed by his lack of momentum toward merging our lives.

Yes, he’d welcomed me in his house. So long as I showed up in his world, we were like a happy family of three, cooking dinners and watching movies at home. Except his home wasn’t my home. My actual home was in shambles, neglected, because I spent half my life at his.

I was ready to blend our families. He had excuses. In hindsight, I recognize how his home represented a liminal space, where his wife was physically gone but vestiges of the life they’d built together, remained. The paint colors on the walls, the wool quilt on his bed, the pink mini chandelier in Katy’s bedroom — their home was filled with a lifetime of decisions made. Even after four years, he wasn’t ready to leave it, literally or metaphorically. Intellectually, I understood why. Grief is a strange thing, and a wounded heart knows no timeline. But emotionally, I was depleted from living in the shadow of her ghost. I’d moved my entire world for him. He wasn’t able to budge his toward me, at all.

Finally, spent by the inequities and strain of living a double life, I snapped. Without forethought, I blurted out in frustration, “Get some skin in the game, or get out.”

I can still see the way his green eyes stared into mine, profoundly sad but hard, immovable, resigned.

He got out.

And took Katy with him.

I’m not one to backslide after a breakup. But with him, I do.

I’m back in his arms that final night. He’s telling me how Katy’s been acting out at preschool. She’s getting physical with other kids, so he hired a psychologist to observe her. The diagnosis? Since Katy lost her mother so young, her emotional development was stunted. When she gets upset, she regresses and lashes out like a toddler.

I let this story wash over me. I wonder, did he even mention me or our breakup to this psychologist? Did anyone consider that Katy’s recent outbursts were a result of losing me — the only mom she can remember — and not the tragic death of her adopted mom, who she can’t?

I don’t ask him. Of course he didn’t mention me. He never saw me as her mom.

But I’m certain Katy did.

He shares one more Katy story that night, about a dream she’d recently shared. She dreamed she was lying in her loft bed, as always. Only in her dream, her bed has three layers. My daughters sleep in the middle bed right below her, and her Dad and I lie on the bottom one.

“Isn’t that cute?” he asks.

I don’t respond. My thoughts whirl around that dream, how Katy yearns to feel us all beneath her, supporting her, sustaining her, keeping her afloat and safe and stable. Katy sees me and my children as her family.

The family she just lost.

How does her dad not see that, too?

Since he never saw me as Katy’s mom, he’s blind to our shared sorrow. I’m thankful the room is dark so he can’t see my expression as I get up from his bed and leave his home, for good.

Then I return to my own, and I start to let go.

A mother’s love is mourning. We watch, proud yet helpless, as toddlers steal the babies from our arms and waddle off. Children emerge where our chubby-cheeked toddlers once were. The teens overtake the tweens, and so on. Our role is to help them thrive and soar, and never show how we mourn each motherly loss as they grow to need us less and less.

But for us “acting” moms — the ones who wanted the role for a lifetime, but got cast out mid-series — our grief is different. We don’t get to see if that child grows or soars without us. All we have is the grief, and memories of a child we loved, frozen in time.

We worry about their well-being.

We wonder if they remember us.

We know we have to let it go, even as we still love. As moms do.

I can feel my two teenagers outgrowing their need for me daily. My love for them permeates everything I do and am; they’re the motherhood journey I always longed for and got. And yet. A mom’s love can always expand to include more, and her wounded heart knows no timeline.

I know a part of mine will always hold space for Katy.

*Name changed for privacy.

I could feel your ache. All I can say is that your story has affected all who read it, and obviously you as well.

Just watched you reading this live. I can relate to your grief. Having overcome mine only recently. Wishing you strength and courage with your adolescent girls.

As for Katie... I've observed that few people have consistent memories of small childhood. They often get back to age 8 - 10. It's difficult not to know what she has become. You gave her your best, so that period of safety and innocent happiness are the basis for her further life. Because even if she may not remember, your share is there, deep inside her.